The Art Collection of the French Royal Academy – About the Database

About the Database

This is the database of the project on the art collection of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. The database identifies the objects that comprised the collection in the eighteenth century and establishes where they are preserved today. It offers a wide range of tools for searching, comparing, and analysing these objects.

Collection

Renowned for its temporary public exhibitions, the Salons, the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture also maintained extensive permanent holdings. Over the century and a half of existence (1648–1793), the Académie amassed a collection of more than 15,000 artworks. The core of this collection consisted of reception pieces (morceaux de réception) – works that young artists presented to an academic jury to become members. Additionally, the collection featured Prix-de-Rome-winning paintings and bas-reliefs, commissioned portraits of the Académie’s patrons, académie drawings by student and professors, plaster casts of classical sculptures, miscellaneous donated works of art, furniture, and unclassifiable objects (e.g., skeletons used in teaching human anatomy).

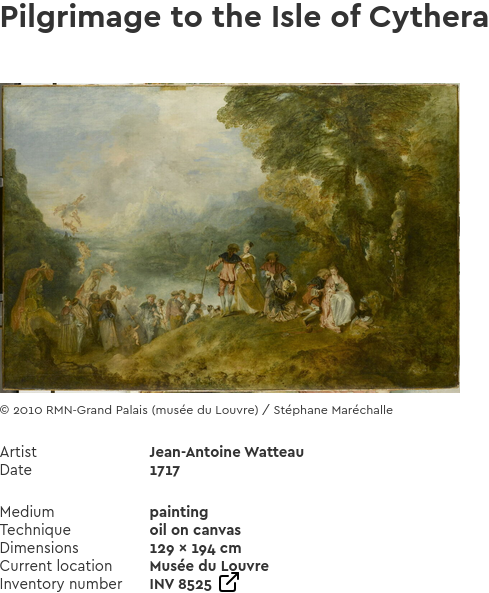

As almost all the prominent artists of the old regime were members of the Académie royale, its collection brought together such iconic reception pieces as Watteau’s Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera (1717), Chardin’s Ray (1728) and Greuze’s Septimius Severus and Caracalla (1769). These and other examination works now offer valuable insights into the institution’s aesthetic values. Académies, plaster casts, and other objects used in teaching shed light on the educational process. While commissioned portraits of the Académie’s patrons and donated works of art illuminate the personal networks behind it. Collectively, these objects show how the most influential art institution in eighteenth-century Europe viewed and positioned itself.

Together with the Académie, the collection changed its home numerous times, moving from the Saint-Eustache to the Hôtel Clisson, to rue Sainte-Catherine, and to the Palais-Royal. However, for most of its history, from 1692 to 1793, it was housed in the Louvre. The hanging of the collection in the Louvre was a remarkable example of eighteenth-century curatorial work and an important “internal” counterpart to the Académie’s public display, the Salon. Unlike the Salon Carré, the main rooms of the Académie were accessible only to exclusive visitors, yet the works they contained served as major reference points for students and members of the institution, many of whom not only worked but also lived in the Palace.

Dispersal

After the French Revolution, the art collection of the Académie royale was dispersed and is now shared by the Louvre, the Versailles, the ENSBA, and many other museums in France and worldwide. The map below shows how widespread these objects are today.

In collaboration with the Centre Dominique-Vivant Denon (Louvre), the INHA, and the Beaux-Arts de Paris, we have worked to reconstruct the Académie’s art collection digitally. This database is the result of that effort.

Sources

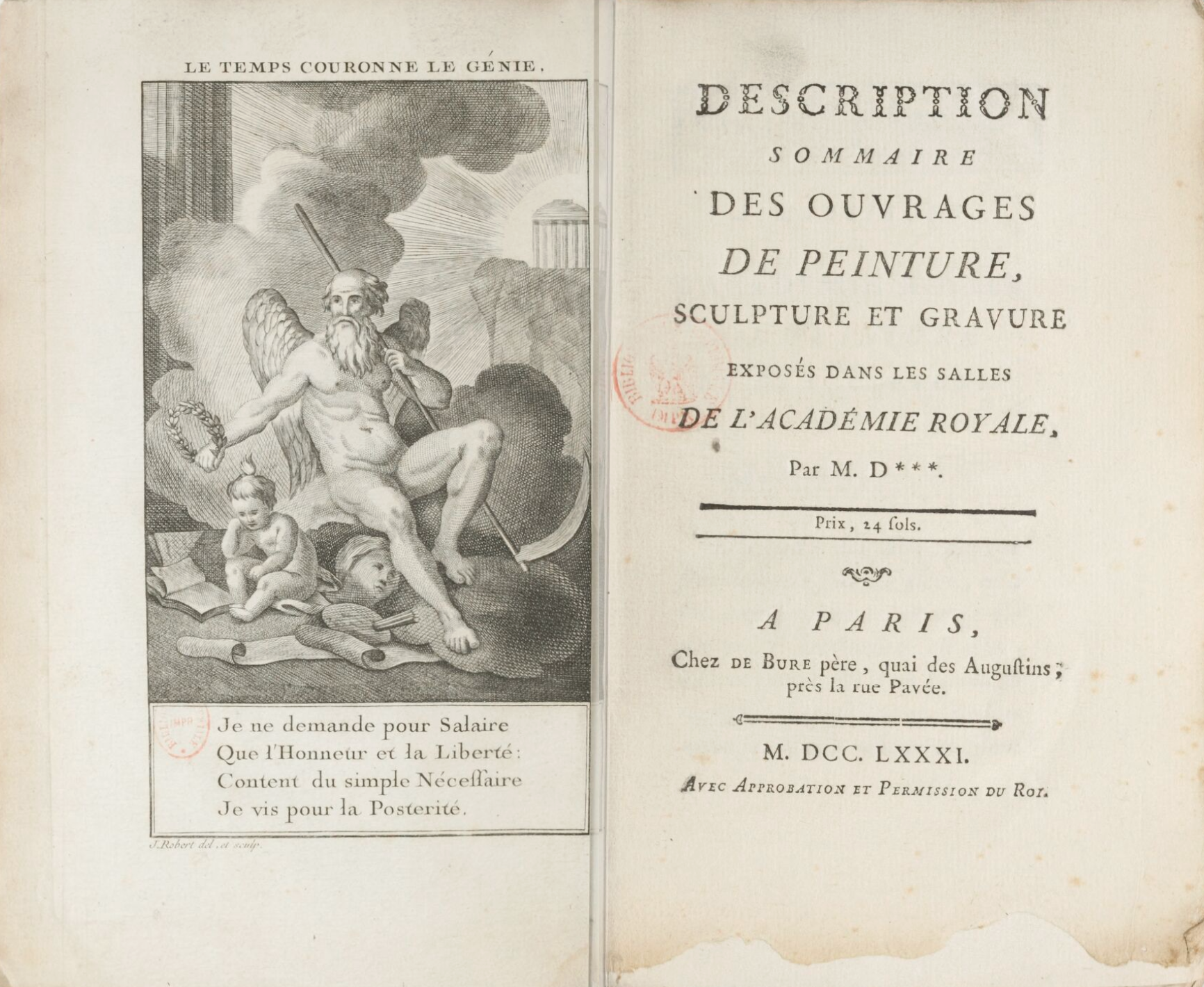

As it stands, the database brings together objects from two eighteenth-century printed inventories of the Académie’s collection: Description de l’Académie Royale des arts de peinture et de sculpture (1715) by Nicolas Guérin, the secretary of the Académie royale, and Description sommaire des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture et gravure exposés dans les salles de l’Académie Royale (1781) by art amateur Antoine-Nicolas Dezallier d’Argenville. These documents provide important information on the collection’s composition and its arrangement in the Louvre but have their limitations. Of the 15,341 objects that belonged to the Académie royale, Guérin lists only 308 and Dezallier d’Argenville 520.

One reason for this incompleteness is that both descriptions were intended as “guides” for external visitors to the Académie, and therefore omit rooms they could not access, such as the life-drawing rooms. These rooms housed a significant portion of the collection, including bas-reliefs and paintings awarded the Grand Prix de Rome, exemplary académies, and plaster casts (from which students drew before proceeding to life-drawing). Similarly, while the vast majority of the Académie’s collection consisted of prints and drawings (totaling over 13,000 of the overall 15,341 objects), Guérin and Dezallier d’Argenville list but a tiny selection, as most were not on display and were stored separately in portfolios.

Another limitation is that Guérin and Dezallier d’Argenville often lack detail in their descriptions, relying on general phrases like “Un buste d’homme” or “Le portrait d’un sculpteur”. This lack of specificity makes it difficult, and at times impossible, to identify artworks. As a result, 65 objects in our database remain unidentified.

Future

To address these gaps, in the coming years, we plan to add objects from three more inventories of the collection:

(1) an inventory dated 7 December 1793, compiled just before the collection was disbanded (Archives Nationales F/17/1267/4)

(2) a 27 March 1775 inventory authored by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, then Treasurer of the Académie royale (ENSBA Ms.39)

(3) an anonymous 1682 inventory, which was added to throughout the early years of the Académie (1690, 1693, 1694, 1697, 1699, 1710, 1712, and 1737) (ENSBA Ms.37)

Integrated into the database, the five inventories will complement each other in meaningful ways, illustrating how the collection evolved over time and how its display changed from the Palais-Royal to the ground and first floors of the Louvre’s Petite Galerie.

Tools

The full-text search allows you to search through artwork titles, artist names, collections where objects are currently preserved, and accompanying notes.

With the acquisition timeline, you can narrow your search to works that entered the Académie’s collection during specific periods.

Filters allow you to sort objects in the database by inventory, type, medium, current location (collection), and original location (room).

By clicking on the “book” icon, you can access primary sources: the 1715 and the 1781 inventories and the academic minutes (Procès-verbaux). The sources open in a viewer that allows you to navigate through the documents and browse their metadata.

By clicking on the “Louvre” icon, you can access plans from the 1715 inventory, enhanced with images of objects from the database. The images are clickable and lead to the corresponding database entries.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Christian Michel, Alicia Adamczak, Élisabeth Le Breton, and Antoine Galley for the information they have kindly shared with us, and Philipp Hones and Deborah Schlauch for their assistance in developing the database.

Sofya Dmitrieva, Anne Klammt, Markus Castor, and Moritz Schepp